When The Heart Is Ready, Grace Will Appear!

J

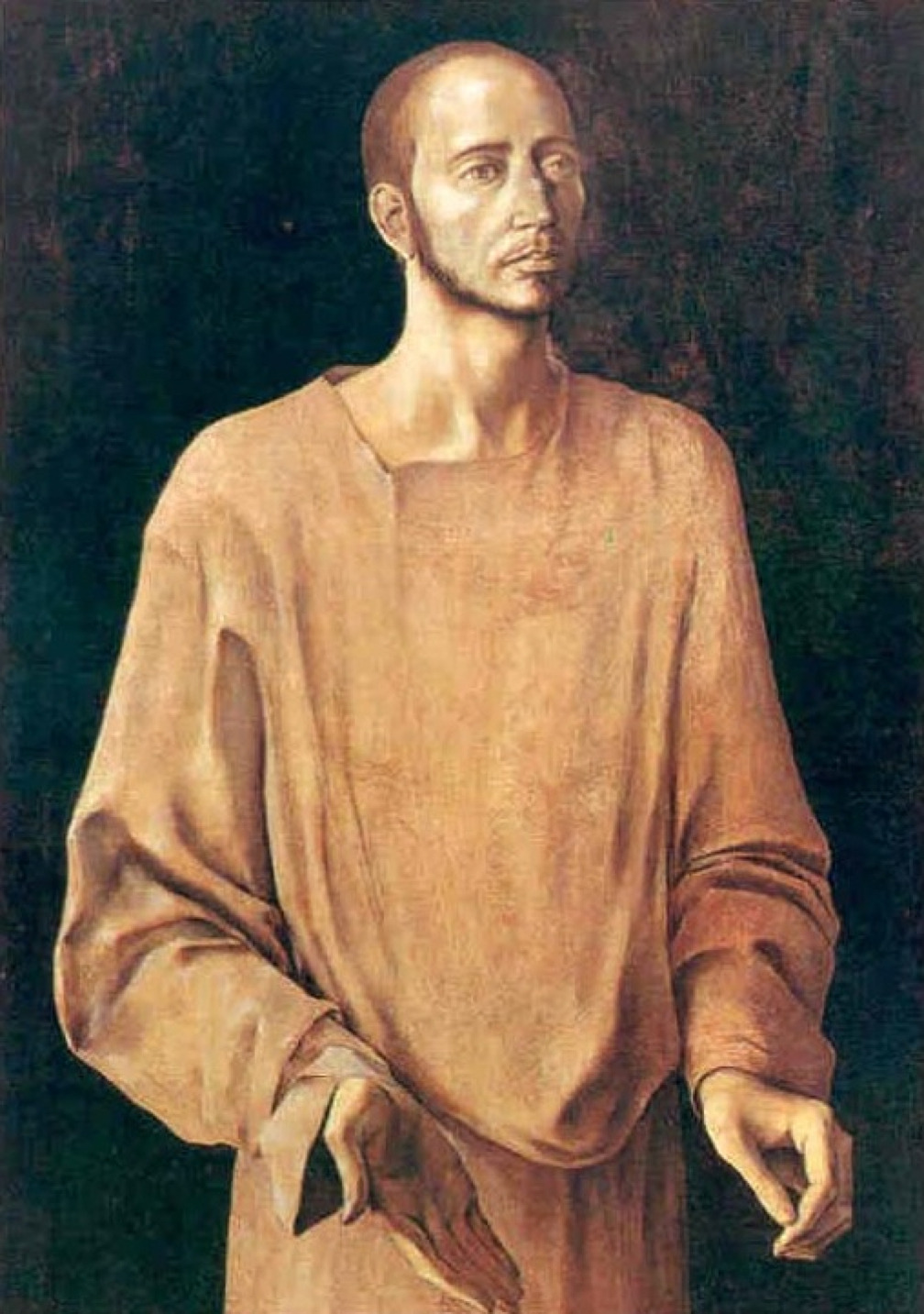

erome Nadal, one of Ignatius’ earliest companions, once remarked that “God chose Ignatius to found the Society of Jesus not because of his virtue, but because of his character—a man of great energy [desire, passion] and magnanimity who never admitted defeat in battle.” Nadal’s insight captures the secret fire needed in the 30-day retreat: to be always moved by great desires.

Ignatius would later exhort his companions, “Let us conceive great resolutions and elicit great desires.” These words were not mere counsel—they were his own story. No desire for the praise and honor of God was too great for him. When he felt moved to imitate the saints, he resolved without hesitation to journey to Jerusalem. When he desired to serve souls, he did not shrink from the years of study it required, though he was already thirty-five.

In the Spiritual Exercises, each prayer time begins with a brief expression of desire to beg for the grace that we want during the prayer. Ignatius asks us to do this. These graces in the Exercises build on one another.

But graces are gifts. There is a proverb from Lao Tzu: “When the student is ready, the teacher will appear.” In prayer, when the heart is ready, the grace will appear. A grace is not something you can plan for. It is not something you can decide on your own. It is a gift. It is grace that God freely gives when the heart is ready.

For our second point: grace does not erase desire—it builds on human desire and redeems and transforms it. Ignatius’ life shows that God works not by extinguishing human longing. From his youth, Ignatius was a man who felt passionately and acted decisively. His imagination and passions were fierce—always drawn toward greatness, even when that greatness was still “vain and worldly.” He once confessed that before his conversion, “I was carried away by a great and foolish desire to win fame.” That same desire for glory would later be purified and redirected toward “the greater glory of God.”

God began to educate his desires. As he read the lives of Christ and the saints, he noticed a stirring within him: “When I thought of the worldly things, I found much delight; but when I thought of imitating the saints, I found joy that lasted.” It was not guilt that converted him, but a stronger desire, a yearning “to do what the saints, like St Dominic and St Francis, had done.”

Grace does not erase desire—it builds on it as its scaffolding. Ignatius’ secretary, Pedro de Ribadeneira, tells a story that warms the heart of any novice director or formator. In the time of Ignatius, there was a novice from Germany who was distressed and thinking about leaving the novitiate. After trying everything else, Ignatius asked him to wait for three or four days, and during that time he was not obliged to keep the de more or the rules. He was given free rein without needing to obey anyone. Ignatius told him that he should do whatever he pleased: he was to sleep as late as he liked and eat whenever he wanted. The novice, with this freedom and gentle treatment, was so moved that he decided to stay. What moved him was that he got in touch again with his original desires. Ignatius wanted the novice to remember what had led him to enter the novitiate. The strategy worked.

And so you ask for the grace. You desire. And Ignatius says that when one does not yet have the desire, then ask to desire the desire. You may have already experienced in your prayer moments when the recommended grace to ask for seems far-fetched. So ask to desire the desire. Even if at first these are impure desires, grace can build on such desires. If God can write straight with crooked lines, then God’s will can often be discovered in our human desires.

We were formed in a spirituality that feared desire and trained us to conceal it. Ignatius shattered that fear by naming the real danger: not desire itself, but desire without order or purpose. We do not fall because we want too much, but because we want the wrong things. Ignatius learned this slowly, as we all do.

This brings me to my third and last point. Ignatius invites us to the Ignatian virtue of indifference. Desire, if it is not ordered or purified, can be disastrous. That is why we need God’s grace again. Grace purifies the heart from worldly attachments. This is the point of the gospel instructions for missionaries to travel light for speed. In Matthew’s gospel, shoes are forbidden. But I appreciate Mark’s version: they may wear sandals rather than go barefoot, for if sandals help them more, they should use them—remaining indifferent and unattached to wearing them.

When we are indifferent to material possessions and even to the praise we receive from the people we encounter in the mission area, we become more obedient, more attuned to the Spirit, and less resistant.

There is a natural tendency that when we stay too long in a mission area, disordered desires also start to develop. When I was first missioned after my ordination, I spent six years in one parish, and I realized the wisdom behind the reshuffling of mission assignments. I was no longer growing, and I felt I was becoming more attached to the place and to the people. When we stay too long in one place and with the same type of people, it becomes much more difficult to be missioned elsewhere. This allows us to minister to others who may not be within our usual circle; indifference works in both directions—freeing us from attachment both to people’s praise and to their rejection.

We beg for grace to awaken great desires in our hearts, to purify and redirect them toward God’s greater glory, and finally to free us through indifference to be sent wherever the Spirit leads. Amen. Fr JM Manzano SJ

Comments

Post a Comment

Thank you for your interest in the above post. When you make a comment, I would personally read it first before it gets published with my response.